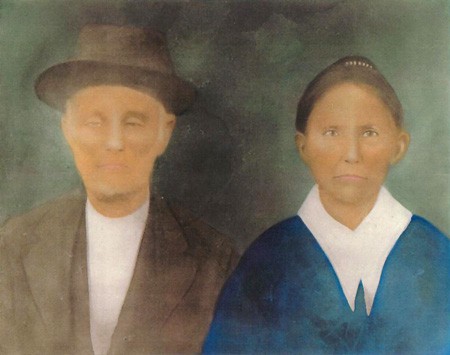

James Pinckney McNabb

1814 - 1893

James Pinckney McNabb & Easter McNabb - Saga of the 1800's From Tennessee to Missouri to Texas back to Missouri Nathaniel Taylor McNabb & Ellender McCubbins McNabb's son, James Pinckney McNabb, b. Feb. 9, 1814 d. June 28, 1893, was born in Carter County, Tenn. and died in Marshfield, Webster County, Missouri. On Nov. 13, 1836 in Brailey City, Tenn. James P. married Easter Flanagan b. 1818 d. after the 1880 census. She was born on the Cherokee Indian Nation in Tennessee and was a full blood Cherokee. She died in Texas where she had gone from her home in Webster Cty. Missouri, after 1880, to tend to her sister who was ill. The family story is that she caught the same illness, died and was buried in Texas, at an unknown place because no one knows the sister's name, where she lived in Texas, or even the year that Easter traveled to Texas. However, James P. & Easter had a son, Nathaniel Armstrong McNabb b. April 2, 1848 d. March 26, 1900, who had moved within 3 miles of Macedonia Cemetery in 1876 & later, in 1900, was buried in the McNabb family plot in Macedonia Cemetery, Lascasas (could be two words) Community, Stephens Cty., Texas, on Ioni Creek, with space left vacant on one side for his wife, Rebecca Ann Turner b. Dec. 24, 1857 d. Jan. 29, 1942, but when Rebecca Ann passed away and the space beside Nathaniel A. McNabb was being excavated, it was discovered that some person in a coffin had already. been buried there so the grave was immediately reclosed. Thus, two things. First, Rebecca Ann McNabb, Nathaniel A's wife had to be buried serveral spaces away from her husband as children were earlier buried in the intervening spaces and second, it is surmised that when Easter died, Nathaniel Armstrong McNabb, her son, was notified and he arranged for his mother's burial in the family plot in Texas, instead of returning her for burial to Missouri. Inasmuch as Easter's burial could well have been 15-18 years prior to that of Nathaniel A. and 55 to 60 years prior to Rebecca Ann's burial, it is quite possible that no one remembered that Easter was buried in the family plot. Few even know why (in 1988) Nathaneil A. & Rebecca are not buried side by side.

Back to the beginning for James Pinckney & Easter McNabb. They had 11 children, 7 boys and 4 girls. They were Albert Houston 1837, Mathew 1839, James M. 1841, Theodore Washington 1843, Mary E. 1846, Nathaniel Armstrong 1848, William A. 1850, Rebecca J. 1852, A.J. 1853, Harriet Ann 1855, Lucretia 1857. James P. as a young man, moved from his birthplace in Carter Cty, Tennessee to the area that would become Bradley Cty Tenn. and thence to the Cherokee Indian Nation and back to Bradley Cty Tennessee all before November 1836 when he married Easter Flanagen. They lived variously from 1837 in McMinn Cty Tenn. to Carter Cty Tenn. to Bradley Cty Tenn. back to Carter Cty. Tenn., then in 1851 to Webster Cty., Missouri. They then moved to Fannin Cty Texas in 1858, to Cooke Cty. Texas in 1860, back to Fannin Cty. Texas, until the end of the Civil War, then back to Cooke Cty until 1867 when with the help of their eldest son Albert Houston McNabb who had come from Missouri to assist them, they returned to Webster Cty. Missouri. James P. had become blind in 1861-62 so remained in Webster Cty Missouri where he accumulated considerable land prior to his death, on June 28, 1893, which was an unusual and accidental circumstance, as follows. After becoming blind in 1861-62 James P. acquired a dog that went everywhere with him & guided him around the many hazards to be found on his Missouri farm. On June 25, 1893 James P. had gone some distance from the house to cut & gather firewood. In the process he became injured but the dog assisted him sufficently for him to make it back to the house. Other family members placed the injured man on a pallet of quilts in the bed of a wagon. Apparently not enough care or skill was exercised and the wagon turned over on the way to Marshfield, Mo. & James P. was thrown from the wagon and died of his multiple injuries on June 28, 1893 & was buried in Timber Ridge Cemetery, Webster Cty, Missouri. Following is a Narrative dictated circa 1871-72 by James Pinckney McNabb to his daughter, Harriet Ann McNabb:

Reader, indulge an old man, sitting in the Evening of Life in Impentrable darkness, in recalling the unpretending incidents of a not uneventful life.

James P. McNabb, the subject of the following sketch, was the son of Nathaniel Taylor McNabb, and was born the ninth day of Feb. 1814. I was raised in the County of Carter, East Tennessee. My father and mother (Ellender McCubbins McNabb) were both invalids, and when I arrived at the age of 13 years, the support of my afflicted parents and family, mainly rested upon my young shoulders. There were nine children of us, 4 boys and 5 girls. When not laboring in home, or in some other profitable way for the family, I would obtain employment from home, yet near by, to get the money to pay for such articles as were really needed in a family, such as we could not manufacture ourselves. Thus my boyhood days were spent in labor and toil, and very few indeed were the hours of leisure.

When cold winter came on, my task was rendered doubly difficult, owing to a lack of even ordinary conveniences and means of performing it. I had to haul fuel on a one-horse sled a distance of half a mile or more, and often through snow from 6 to 8 inches in depth; and rails by the same conveyance through the sleet and storms of winter; a distance of a mile. The school boy at his comfortable desk and fireside, surrounded by joyous, happy companions mingling with him in a generous rivalry in the pursuit of knowledge and pleasure, knows little of the hardships that bow the shoulders, sadden the hearts and dim the eyes of youth as sensitive, ambitious and capable as themselves, that by the frowns of adversity are forced to take upon them tasks that try the courage and test the fidelity of manhood. What need have I to mention the toil, exposure, suffering, anxiety, the weighted upon my young heart, during those long years. Ask the parent, the head of a family, what it is to feel the responsibility of providing for a large circle of helpless ones, and feel that his two arms are their main stay and shield. Throw this load upon the shoulders of a lad that in years is little more than a child, and you will have some conception of burdens that made a stout, bold young heart prematurely thoughtful and grave. I speak not so much of the bodily, physical hardships and toils -- they were severe enough, and if they had been lightened by the pleasures pastimes, and merriment that belongs to youth, of themselves they were nothing, but the hard necessity that robs youth and boyhoods of its mirth and gaiety, is the saddest, and hardest to be borne.

I would not have my kind-hearted reader believe that I recall these scenes of my early life with one thought of bitterness or regret. I feel now, as I felt then, that all the hardships I suffered and endured were duties --responsible duties, that I owed to an afflicted father and mother, and my brothers and sister, who were unable at that time make their support.

After a time, a younger brother had grown large enough to assist me in providing for the family, and his assistance afforded me some spare time to work for myself. And being thus relieved by the help my younger brother, when I became of age, I was the owner of a a saddle and bridle; -- and kind reader, I would not have you believe that I had in anywise neglected the duties due my aged and afflicted parents, in thus becoming the individual owner of a horse; this little spec of wealth, of which I was now the sole proprietor, was the accumulation of spare hours earned by extra exertions and denial.

My younger brother (Nathaniel Taylor McNabb II b. 1818) being now 16 years of age, I left home (1834), in search of employment. I had an elder brother (Alfred W. McNabb, b. 1809 ), a Mill-Wright, living 200 miles from father's, and cheered with bright and glowing prospects for the future, I journeyed to his home--not on a whirling lightning express train, as the world today joumeys, but on the patient back of my gentle horse, comsumming days, where now a like trip would not require as many hours, reached my brother's house about the last of Oct. It was some disappointment to me to find that my brother was not working at his trade. He promised me, however, that if I would do his _alls work and help him gather his crop, he would find employment for us both by the close of the year. Acting upon his assurances, I remained with him, and freely rendered the assistance he desired.

At the close of the year, I was without money, and to my surprise as well as mortification, the promises of my brother proved a total failure. At this unhappy and unlooked for result, I left my horse with my brother, and started afoot for a little town in Georgia by the name of Rome, and reached it the following day. Here I found employment at $12.50 per month, and after working 6 months, received a letter from my brother, requesting me to come and get my horse, as he intended moving back to my father's. Rome was 100 miles distant from my brother's. I left Rome with the intention of going back to my father's by the way of my brother's, but when I reached the home of the latter, I found him making arrangements to move to the Indian Nation. Here again, was a sad disappointment to me, and I am finally yielded to the urgent solicitations of my brother, and went with him to the Indian Nation. My brother, promised me an equal share with himself in farming or in any business in which we might engage.

We reached the Indian country about the first of March and we fenced and cleared about 20 acres; and just as we were about to pitch the crop, there came a man from a considerable distance, to employ my brother to build a mill; an agreement was made between them, and I, of course, had to remain at home and cultivate the crop, and take care of his family. To a young man as I then was, the life I had to lead was very confining. Living in an Indian country, I had to stay close at home, day and night. When not engaged in the crops, I employed myself in clearing more land for the next year's cultivation. One whole year had rolled away ere my brother returned to his home. He came home with plenty of money. I received for my years salary $11.00 in money, and a something else besides, too insignificant to mention. Existing circumstances, as well also, the persuasions of my brother, influenced me in uniting with him in the cultivation of another crop. In the fall, as soon as the crop was matured, we divided the effects. I then built me a house, moved into it and lived alone about four months.

It would scarcely seem necessary to say to my reader, especially if he be blessed with sharp perceptive faculties, that my new house indicated a worthy and sensible purpose. Being now married (m. 1836) and living at home, I partially forgot my past trials and troubles, but it was not long before a sad accident befel me. On the 29th day of March, 1837, I was engaged clearing a piece of timbered land, and while dislodging a tree that had fallen against another, I was severly wounded, and rendered unable to work for nearly a year.

It was now three years since I had seen my father and famly; I concluded, therefore, as soon as I was able to travel, to go and see how they were getting along. I found them living an unfavorable, and I might say uncomfortable condition. My younger brother had left them and had been gone nearly a year. My father insisted that I should come and take care of him as he was in a helpless condition. I returned home, and it was a year before I could make arrangements to pay them another visit. I found my father enthralled with debts, and much reduced in circumstances. I went back home, and returned with my family to my father's, erected for myself a good hewed log house on his premises, and with my own money discharged the principal and most pressing debts against him. And, generous readers, owing to misfortune I had gained only about $300 in my three years absence; but although my portion was but scant, I gave it with good will.

My attention was first directed towards making repairs, and in arrangements for seed-time and harvest. By the time I had made one crop, all my means were exhausted, and the experience of one crop renabled me to see most clearly that on such land in that old country, I could not support two families, and consequently, in the spring of 1840, I moved back and settled in the woods, not far from the place where I was married, to obtain a pre-emption on 160 acres with an allowance of twelve month's time in which to make the payments. Money was scarce, and the prices paid for labor extremely low, and when the twelve months expired, I had just money enough to pay for 80 acres. One of my neighbors prevailed on me to borrow the money and pay for the remaining 80 acres for him, and I did so, acting under assurances from him, that the money would be refunded in a very short time. The short time never came, and I was soon made to feel home that my own little home was placed in a critical condition. The time for making the payment was fast approaching. I went to my neighbor, and spread before him in a clear and truthful light, the condition in which I would soon be placed, if he did not raise the money. I had borrowed for him, and he paid me in words; total inability, total insolvency, and total do nothing. Times were hard, money extremely scarce, and prices for labor almost nothing. I went to a merchant a man of wealth; I stated-the case to him; he listened patiently, and without hesitation, gave me all the money I wished on twelve months time. I then paid my neighbor for his improvements, and took the land. In six months from the time the friendly merchant let me have the money, I paid the debt; money earned by hard labor, and at low prices.

After the foregoing trials, troubles and disappointments, I did not falter, kind reader, in my efforts, but on the contrary, in the heat of summer, I split rails at twenty-five cents per hundred and found myself, to provide the necessaries of life for my then helpless family. We had seven in family, and our circumstances reduced to almost nothing. And now it was that I was brought to meditate upon the vanites of all earthly treasures; That thirty years had now passed away, all, all of it wasted in worldly pursuits, of no real nor lasting importance, and that now I found my self a complete wreck in the midst of it all. The more I reflected on the past, the more I was convinced of the sin and folly of my past life, and that I was now enduring a severe but merciful chastisement. Kind reader and friends, the more I thought, the more I felt the weight of Divine displeasure; my eyes were being opened to a sense of sin and unworthiness; and I trod the path of prayer as a humble penitent search of forgiveness. I obtained it. The quickening influence of God's Holy Spirit, was enkindled in my heart. I was happy and rejoiced I sought the House of God, the Methodist Church, and my name was en rolled as a member. Twenty years have elapsed since then, but not a moment I have not felt composed and resigned to our Heavenly Father's will, and now, beloved and gentle reader, before I leave this subject, let me entrest you, as warmly and earnestly as I would my own dear children, to direct your thoughts to purer, loftier, and holier scenes; put our trust in God's Holy Word, full to overflowing, with the richest treasures, make sure work for the Kingdom of Heaven, and you will be happy amid the direst calamities of earth.

In the fall of 1851, I huddled together my little effects, and emigrated with my little family to Missouri. I settled in the woods near Pleasant Prairie in Webster County. A yoke of oxen, one wagon, and $60 in money, completed my worldly wealth. The winter was very cold and severe, and our prospects seemed unpromising, but the people were friendly, and treated us with great respect. The opening spring was cheering to us all. I went to work in good earnest, cleared ten acres of ground, fenced it and put eight acres in cultivation, rented six more of a neighbor, and for strangers in a new land, all things seemed to move on smoothly. My oldest son was hired out, and a certain man took occasion to treat him with disrespect. I went over to reconcile matters and was treated in the same manner. "Our meeting terminated pugilistically. He sued me at law, and his own neighbors paid the cost and fine for me. I make use of the uncommonly long word "pugilistically," to hide within its folds, even from myself, the deep shame and mortification I feel, and to me this word sounds less harsh, and seems to weaken the force and strength of the fact.

Our health continued good for two years after our arrival in Missouri. From this time, and for five consecutive years, sickness continued its inflictions upon us, and in September 1857, the spirit of our beloved son Mathew took its flight from earth to brighter realms above. Anxiety, fatigue, and loss of sleep prostrated me on a bed of sickness, and when I recovered I resolved to leave Missouri, as soon as I could, in search of a milder and more uniform climate. I left Missouri for Texas, in the fall of 1858, and reached Fannin County with my family, ten in number, and with five cents in my pocket. I had five head of horses to winter, and only five cents to begin with. I rented land of a man who was going to Tennessee on a visit. He left the place and the stock in my care. I was told by several, that this man of whom I rented, was under a bad character, but my necessity compelled me to hold on and risk the consequences. I broke a number of acres with a four-horse team, and pitched a crop. But before harvest the man returned, seemed much pleased with what I had done, and we made an agreeable settlement. I continued with him, sowed wheat, and rented the place for another year. After I had made all the preparations for another winter, he told me he wanted the place for his cousin. I consented, rather than have a difficulty, and sold him my wheat crop. My neighbor's words finally came true, for when pay-day came, he fraudulently deprived me of my wheat crop.

The next season, I rented land of a neighbor, and he was a gentlemen. I cultivated the crops on his land. I now determined to go in search of a piece of land where I could get water and timber convenient. I found it in Cook County (Texas), and moved my family in August 1860, and sheltered under tents on the land until I could erect a building. We were now living 80 miles from Fannin County (Texas). When our house was suffiently comfortable, I returned to Fannin County, to gather my crop and haul it home. My crop being all saved and smugly stowed away at home, I commenced preparations for a crop the coming year on what I now considered my own land. We were all together and ten in number. I had labored for many years, and I felt now more than ever before, that a bright prospect was opening for a quick comfortable and happy home. Meeting together at night, after the toils of the day were over, we would talk over our past reverses in life, humbly kneel to God our Heavenly Father, and retire to rest with peaceful hearts, and composed minds. My little stock was increasing around me, my home, though plain, was snug and comfortable. There was land in abundance for my children to settle around me, and be near me in my old age. I was at peace with God -- felt that I had wronged no man, and dear, reader, for one like me who had gone through so much tribulation; my home felt to me somewhat as though it were within the gates of Paradise.

Oh! how painful to me now to recur to what at first only seemed a trifle, but which finally culminated in a serious calamity. In June, 1861, I was taken with the sore eyes, and was confined for some weeks to the house. In Novembe I. was taken with neuralgiac pain in my head and eyes, and in a little time lost my sight. In the spring of 1862, my sight partiely returned, but in July the pains returning, I was again struck blind. The war was now raging with desperate fury; the conscript law was in force; my son, on whom I chiefly depended, enlisted to avoid the conscription, and my other son who was married, also enlisted, and I was left, a blind man in the midst of a helpless family of boys and girls. To heighten the scene of desolation around us, we were living upon the confinds of the Indian District, and they had extended their work of murder and plunder to within a short distance of us. They commenced their dreadful work of murder, arson and plunder, in the fall of 1862, and in the spring of 1863, they completed a scene of murder and outrage, within a mile of our house. Our hopes of safety seemed only in flight, and we traveled away as fast as we could, and did not stop until we had gone 80 miles. Learning shortly after, that a regiment of soldiers was stationed near where we lived, we returned to our home. Shortly after our arrival here, I heard that a skillful Oculist was at Paris, one hundred miles distant, and I obtained a mode of conveyance to Paris, hoping to have my sight restored. The physician sold me medicine, but gave me little or no encouragement, and the man who took me there left me at a tavern. In a short time I was favored by a stranger, who took me in his wagon, as far as the residence of my brother-in-law, within 80 miles of my home. I had been from home about a month. I got a conveyance as soon as I could for I was filled with concern and anxiety about the safety of my family. On our way, at a place where we stopped for the night there was a woman, a stranger, whom I never shall forget. She was a boarder in the family, and had the appearance of being a woman of wealth. Her kind and gentle manners towards me, and words of sympathy, are what I never shall forget, and shall ever love to remember. On leaving the next morning, she offered me money, which I refused to take, saying "that I had enough for present use." She so urged it upon me that I finally accented $1.50 to manifest my appreciation of her warm and generous feelings. This trip in search of relief cost me $50, and I reached home as I had left it, a blind man, but not disconsolate, for amid the vanity, trials and afflictiors of this life, the soul at peace with its God, rejoiceth, and will rejoice from everlasting to everlasting.

Reader! I was now at home again, and the idea of home carries with something that is comforting and soothing to the breast of every one. One of my sons (James M.) who had joined in the war, was now at home on a sick furlough (Fall of 1863). The Indians had again renewed their ravages and work of destruction, and helpless citizens were now in a state of dreadful consternation. No one had a home of safety for even a single hour. Little groups of aged men and helpless women and children, were to be seen, in every direction collected together by feelings of instant concern. The causes of fear and alarm increasing, our family was rescued by some of our neighbors and we remained with them all night; the next morning my son who had returned home on furlough, went back to see about the horses we had, a band of 150 or 200 Indians discovered and pursued him; once in safety, and now panic-struck with fear, all of us fled quickly as we could to a neighbor's house one mile and a quarter distant. In the house there were huddled together about 60 persons, men women, and children, and very soon the house was surrounded by a bout 180 Indians. There were not over twelve men and boys in the house that were able to give the least protection, and these manifesting so much alarm, caused the women to make an attempt to escape to the woods. At this time, the Indians, being in a body above the house, we managed in making our escape, trying to keep the house between us and the Indians. I was scarcely able to travel, and felt sure of falling a victim to the savages. My dear little daughter, Rebecca (b.1852), of ten years, clung to me all the time. I entreated her to leave me and save wherself by keeping up with the rest; that my strength was almost gone and there seemed but little hope of my safety. But the love and fidelity of this dear child, was not to be overcome by fear or persuasi on. My son assisted me, and we made our escape. The news came that there was a company of fifty soldiers in pursuit of the Indians; that they were in close pursuit. The Indians fled to a high position on the prairie. The soldiers advanced on them and an engagement ensued. The soldiers were driven back a short distance, three of their number being killed, and three wounded. The soldiers soon rallied for a second conflict, advanced and fired on the Indians, who fled, murdering, burning, robbing, as they went. My house with its contents was burned and-horses bout the time of our flight from home, Christmas week of 1864.

We were now adrift in the world, with simply the chothes we wore. Every house and home was being deserted. A large number of us under the guard of soldiers, were taken to a little town (Marysville) about 15 miles distant. It was now winter, and we had but three quilts which were given to us, and one blanket that I usually wore as an overcoat We left the town the next morning for Fannin County, where we rented land and managed to live in a very hard way, until the war closed. My family now wished to move back to the place we had lived in Cook County. We returned to our old place. The County had been made desolate by the Indians, but now, (in 1865) settlers were straggling back to their old bomes; but in the fall several outrages were committed by the Indians, which much alarmed and finally compelled the settlers to "Fort up," by building a number of cabins very close to each other. In the spring of 1866, we pitched a crop, and during the crop season, my son who had been in the army, married, and very soon thereafter sickness came upon us, and we were all helpless, and the stock destroyed the crop efter it was mature. It was now the fall of the year, and myson (Albert Houston McNabb, b.1837) who had remained in Missouri came to see us. As the Indians were still troublesome, he advised me to sell and remove to Missouri.

On our way to Missouri (1867), whilst passing through the Indian Nation an incident occurred, which wrung our hearts with the deepest distress. While in camp on a high (bluff) my oldest son with my two youngest girls went some distance to a steep declivity for some water. On returning up the bank, the elder girl (Harriet) slipped, and was carried in a gently rolling manner down the hill some distance. To avoid the prededing accident, she thought she would go some distance round but in circling round lost the direction to camp. In anon, after she was missed, and the loudest calls were answered by the echoes of the hills and forest. No tongue can express the anguish of our hearts. I was blind and could not look after the little wanderer. After three, or four hours harrowing suspense she came bearing in her hand, a pine bush, which a man present, affirmed could not have been obtained nearer than three miles. The child stated, that when she found that she was lost she listened to hear the ox bell, and having wandered from hil to hill she at last came to a house on a road, and was there directed to our camp.

We reached Missouri with three horses, three yoke of oxes and a wagon. One of the horses died and the other two strayed or were stolen. My youngest son (William A. McNabb, b. Dec. 1850.) remained with me until 1869. I have with me now, my wife and four daughters; and my sons are all gone. My youngest daughter is my help and guide, religion is my comforter, and God is my hope.